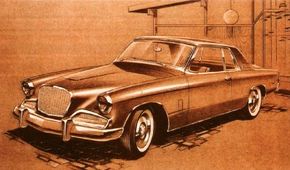

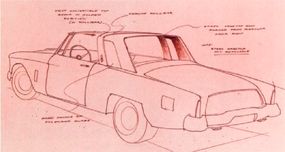

As part of the plan to keep Studebaker in the auto business, Sherwood Egbert called on Brooks Stevens to update the Hawk. With little time and less money, Stevens created the stunning Studebaker Gran Turismo Hawk.

Advertisement

An enraged Raymond Loewy rushed to a phone when he first saw the new Studebaker Gran Turismo Hawk at the 1961 Paris Auto Show. He couldn't understand how Studebaker could have allowed Brooks Stevens to modify his firm's 1953 Studebaker Starliner design so extensively. Fortune magazine had called it "one of the hundred best designs of modern times." In his transatlantic call to South Bend, he demanded to know what had happened and how.

Studebaker executives, however, realized the wisdom of their decision and stood by Brooks Stevens' new design. Loewy, busy with the Avanti project for Studebaker, dropped the matter.

Only infrequently has a face-lift not destroyed the purity of an original concept. Stevens' heroic restyling of the Starliner is an example of the rare exception ("heroic" because Stevens accomplished the task on a shoestring budget and in very limited time). His 1962-1964 Gran Turismo Hawk emerged as a refreshing, timeless design that looks as good today as when it first debuted almost 50 years ago. And Stevens' design took nothing away from the Starliner, for when parked side by side both cars still look "right."

When Stevens was called to South Bend, Studebaker -- the oldest vehicle manufacturer in the U.S. -- was on the ropes. It had made wagons since before the Civil War, but now pressures were mounting, from within and without, to abandon automobile production. Some say Studebaker had been slowly dying ever since its brush with bankruptcy in the 1930s. But material production had brought in a lot of capital during World War II, and the future looked promising in 1946.

The challenges and opportunities were there. The problem was that management consistently took the wrong turn at every crossroad. In some ways, the company was ahead of its time, as with its late Forties and early Fifties association with Loewy. In other aspects, it seemed woefully out of date, especially in some areas of engineering.

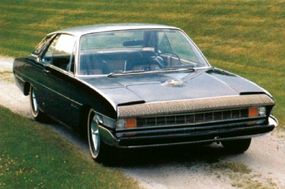

Ford is generally given credit for creating the sporty "personal-luxury" market with the 1958 Thunderbird, or "Squarebird." Its basic dimensions seem to have been borrowed from General Motors' Autorama dream cars of the mid-Fifties, but GM didn't enter this segment until Pontiac fielded the 1962 Grand Prix -- or mid-1961, when Olds debuted the Starfire.

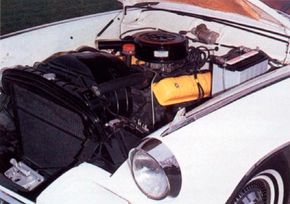

In fact, Studebaker beat both Ford and GM to market in 1956 with the sporty, well-trimmed Hawk. Although really a makeover of the 1953 Starliner, the Hawk was both a good performer and a good looker, particularly the top-of-the-line Golden Hawk.

Studebaker called it "a sports car...that restores the fun and excitement to luxury motoring." Only later did others invade that market niche -- 1958 T-Bird, 1963 Riviera, 1966 Olds Toronado, 1967 Cadillac Eldorado, and others -- but Studebaker could lay claim to being the first of this lineage.

Studebaker was in financial trouble as the Hawk was being developed. Learn how Egbert kept the ball rolling during difficult times on the next page.

For more information on cars, see:

- Classic Cars

- Muscle Cars

- Sports Cars

- Consumer Guide New Car Search

- Consumer Guide Used Car Search

Advertisement