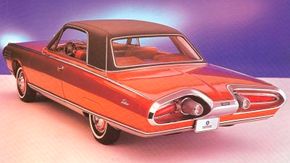

Many remember the Chrysler Turbine Car, the bronze-colored hardtop that looked like a Thunderbird and whined like a banshee. But that copper rocket was just one result of a broad development program that produced a remarkable number of 1950s and 1960s Chrysler Turbine concept cars.

The program seemed to promise that turbine power would soon be in your driveway -- as indeed it was for the couple hundred people who drove the 50 Turbine Cars built in a three-year consumer test program. But though Chrysler came closer than anyone to perfecting a practical turbine automobile, events rendered the futuristic powerplant just so much hot air, and its promise went unkept.

Advertisement

The gas turbine relates to the jet engine, patented by England's Frank White in 1930. Rolls-Royce speeded the development of jet fighter planes, which came too late to significantly affect World War II but which proved decisive in Korea.

Between those wars, America's Big Three automakers began working on aircraft turbines (Chrysler built a turbo-prop for the U.S. Navy Bureau of Aeronautics in 1948), but didn't begin thinking about roadgoing applications until the mid-Fifties, perhaps inspired by Rover of Britain's 1952 experimental turbine car. Of the Detroit producers, only Chrysler seemed as serious about turbine-powered automobiles; Ford and GM put most of their turbine emphasis on trucks.

Like a jet, the turbine's basic element is a wheel ringed with blades or vanes; a fuel/air mixture flows past the vanes, causing the wheel to rotate and produce power. In many designs, including most of Chrysler's, this "power turbine" also ran a "first-stage turbine" linked to a compressor; the latter, of course, squeezed the mixture for firing, which was accomplished by a spark plug-like device called an igniter.

This simplicity appealed greatly to Chrysler and others because it meant fewer parts, which implied less maintenance. For owners, the turbine promised operating smoothness unknown in reciprocating engines, because it produced rotary motion to begin with.

Other attractions included near instant warm-up (and available engine heat in winter), dependable cold-weather starting, the ability to run on a wide variety of fuels (Chrysler claimed the turbine could gulp everything from peanut oil to Chanel No. 5), negligible oil consumption, and no need for antifreeze.

Offsetting these pluses were four big minuses: high internal heat (upwards of 2,000 degrees Fahrenheit); operating traits better suited to steady speeds, as in aircraft but typically not cars; no inherent "engine braking," vital on the road; and high oxides of nitrogen (NOx) emissions. Nevertheless, Chrysler would solve or at least minimize all of these problems over some 25 years of development.

High heat was the biggest problem. To attack it, Chrysler engineers under George Huebner, Jr., soon known as Highland Park's "Mr. Turbine," developed what they termed a "regenerator." This was essentially a rotating heat exchanger that removed exhaust-gas heat to reduce internal temperature and boost fuel mileage above what it would be otherwise.

Also studied early on were improved operating flexibility and development of materials resistant to ultra-high temperatures.

Learn about the development of Chrysler's turbine engines on the next page.

For more on concept cars and the production models they forecast, check out:

- Concept Cars

- Classic Cars

- Consumer Guide auto show reports

- Future Cars

Advertisement