The Great Depression had cast a long, deep shadow over America by 1933.

Those who attempted to shake off the gloom by attending the World's Fair in Chicago saw three very special autos, not the least of which was a Pierce-Arrow; however, the 1933 Pierce Silver Arrow would soon be introduced.

Advertisement

The 1930s may be hard for many to comprehend now, but the facts are there for all time. By 1933, America was a nation looking for work. Unemployment ran one in four nationally and was much higher in cities. Banks were shut against depositors unable to get at their own savings. Former millionaires were begging for low-wage jobs.

There was no government-sponsored work relief, let alone medical- or family-aid programs. The record seems to indicate that Franklin Delano Roosevelt probably did not save the republic for capitalism, but those who remember the Threadbare Thirties can be excused for thinking he did.

Whatever the success or failure of his programs, FDR imparted something else that was, in the end, more important: hope. Still, it took a new world war to end "hard times" for good.

The automobile industry reflected the national misery. From a healthy 4.5 million cars in 1929, annual production slid to barely a million in three years.

Ford, which had once built 1.8 million cars in a year, settled for 335,000 in 1933. Among smaller manufacturers, bankruptcies, mergers, and desperation tactics were legion. The Great Depression was especially hard on luxury makes, whose market almost disappeared.

Peerless and Marmon, two of America's grandest marques, built beautiful Sixteens that nobody wanted, and both companies were gone by 1933. Even their stronger competitors had trouble. It wasn't simply that former Cadillac, Packard, and Lincoln customers could no longer afford those cars -- many had marshalled their money and insulated themselves from the slump -- but that those who could simply preferred not to be seen in them.

For a couple of years after the Wall Street Crash, the nation acted stunned, for it had never seen anything like this before and its leaders seemed powerless to cope.

Slowly, however, the country's spirit revived, and though the economy only got worse into 1933, institutions public and private began putting on a brave face, fearing nothing but fear itself, projecting dreams of a bright new future just around the corner.

Roosevelt signed the Federal Emergency Relief Act and an alphabet soup of other "New Deal" programs, Hollywood produced 550 films (one of the few entertainments people could still afford), Robert Byrd began his second South Pole exploration, Sir Malcolm Campbell broke the land speed record at over 270 mph, the New York Giants beat the Washington Senators four games to one in the World Series, and Chicago proclaimed a "Century of Progress" at its World's Fair Exposition on the shores of Lake Michigan.

Auto manufacturers looked upon all this with their traditional enthusiasm, trying to comprehend how they might turn disaster into opportunity.

Luxury-car makers dealt with the situation in various ways. Cadillac, though sheltered under the large General Motors umbrella, cut back hard on production, but Lincoln output tapered almost to a halt, then was restored by the streamlined, medium-priced Zephyr starting in 1935. Packard, still proudly independent, sought salvation with its slightly lower-priced 1932 Light Eight, failed, then planned a still-cheaper volume product that emerged in 1935 as the company-saving One Twenty.

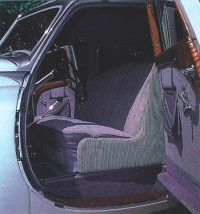

All three of these leading luxury makes brought out specials and show cars for the round of 1933 automobile shows, culminating with the Chicago fair. Their onetime archrival, the still highly respected Pierce-Arrow Motor Company, followed suit with its own stunning creations.

Continue to the next page to learn more about the Pierce-Arrow Motor Company and its automobiles.

For more information on cars, see:

- Classic Cars

- Muscle Cars

- Sports Cars

- Consumer Guide New Car Search

- Consumer Guide Used Car Search

Advertisement