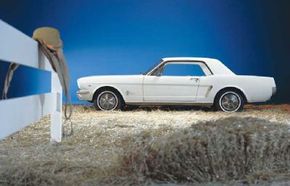

As the launch of the 1965 Ford Mustang approached, Ford was confident its new sporty car was on target. Its job now was to let the country know about this new kind of car. The introduction of what popularly would be known as the 1964 1/2 Ford Mustang was an encompassing and brilliant marketing blitz. America had scarcely seen anything like it.

With the curtain poised to rise in early 1964, Dearborn marketers shifted into overdrive to get the public ready for Mustang. Though Ford previewed the showroom model at a January 1964 press conference, it put the information revealed under an "embargo," meaning reporters weren't supposed to go public with it before a date Ford had set. This tactic is still widely observed in various industries, a sort of cat-and-mouse game between manufacturers and the Fourth Estate.

Advertisement

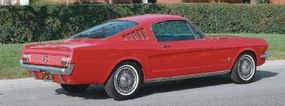

The Big Day ArrivesThe weeks leading up to Mustang's debut saw big stories in all sorts of places: Business Week, Esquire, Life, Look, Sports Illustrated, U.S. News & World Report, The Wall Street Journal -- and, of course, almost every "buff book" car magazine. Finally, the wraps came off. On April 16, Ford presented its new baby to some 29 million TV viewers, buying the 9 p.m. slot on all three networks. Friday, April 17, was the public rollout. That morning, 2600 newspapers ran announcement ads and articles while the Mustang was revealed to opening-day visitors at the New York World's Fair.Ford invited some 150 journalists to the unveiling -- and some sumptuous wining and dining. The next day, it set them loose in a herd of Mustangs for a 750-mile cruise to Motown. "These were virtually hand-built cars. Anything could have happened," a Ford official remembered. "Some of the reporters hot-dogged the cars the whole way, and we were just praying they wouldn't crash or fall apart. Luckily, everyone made it, but it was pure luck."

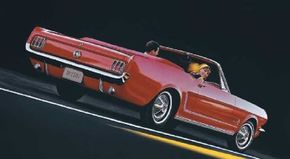

The publicity blitz didn't end there. A flood of print and TV advertising insured that almost everyone in America knew the "unexpected" Mustang had arrived. Ford also stoked public interest with numerous promotions and events. A highlight was getting Mustang named official pace car for the 1964 Indy 500. Though a white convertible with blue dorsal racing stripes led the field on Memorial Day, Ford built another 35 ragtops and some 195 hardtops decked out in the same regalia. The convertibles were later sold, the hardtops given away in dealer-sponsored contests.

It all added up to a not-so-small fortune, but the money was well spent. Mustang caused more excitement than any Ford in a generation. It surely provided a welcome mood lift for a nation still coming to terms with the assassination of President John F. Kennedy the previous fall.

For even more on the Ford Mustang of yesterday and today, check out the following articles:

- Saddle up for the complete story of America's best-loved sporty car. How the Ford Mustang Works chronicles the legend from its inception in the early 1960s to today's all-new Mustang.

- It was the right car at the right time, but the Mustang had to await the early 1960s, when a savvy Ford exec realized the Mustang's potential. Learn how Lee Iacocca brought his "better idea" to life in 1965 Ford Mustang Prototypes.

- By 1967, the original ponycar was no longer the only one and had to fight for sales. 1967, 1968 Ford Mustang details the fresh "performance" look and go-power that made a million-seller even better.

- The Ford Mustang is central to America's muscle car mania. Learn about some of the quickest Mustangs ever, along with profiles, photos, and specifications of more than 100 muscle cars.

Advertisement