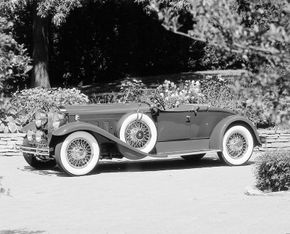

For many people, Packard was, in its heyday, "the supreme combination of all that is fine in motor-cars." It may not have always been the technical "Standard of the World," but it was the social Standard of America, even for millions of would-be buyers who could never afford one.

In 1929, more people owned stock in Packard than any other company save General Motors, and there were far more Packard stockholders than Packard owners.

Advertisement

Packard got its start in Warren, Ohio, in 1899, when James Ward Packard figured he could build a better car than the Winton he had purchased. His first was a small one-cylinder model with automatic spark advance. James B. Joy took over the concern in 1901 and moved it to Detroit in 1903, the year of the first four-cylinder Packard.

The car that moved Packard firmly into the industry's front rank was its 48-horsepower Six of 1912. Packard then leap-frogged Cadillac's new 1915 V-8 with a V-12 the following year -- the fabled "Twin Six," though that only lasted until 1923. A new straight-eight arrived for the 1924 season. Packard did introduce a less-prestigious Six in 1921, but that was dropped well before 1930. The make then maintained its reputation mainly with eight-cylinder engines right on through its sad death in 1958.

For a company so single-mindedly devoted to luxury, Packard compiled a remarkable production record. It regularly outproduced Cadillac in 1925-30, even though its GM rival had help from LaSalle beginning in 1927. Except for 1931, '32, and '34, Packard continued to out-build Cadillac/LaSalle until WWII.

Like other luxury makes, Packard relied on middle-priced products to survive the Depression, most notably the One Twenty, new for 1935. This, together with the companion One Ten, enabled Packard not only to endure "hard times" but to grow rapidly from low-volume luxury to true mass-market producer. Unfortunately, the firm was far slower to abandon medium-price products after World War II than either Cadillac or Lincoln, thus sowing the seeds of its ultimate demise.

In 1923, Packard began using a "series" number to designate each year's model line, a practice it continued into the '50s. Historians have since converted these to model years for ease of recognition. The Seventh Series, for example, coincides with 1930.

That hierarchy began with a standard Eight, which had the least-pretentious bodies on relatively short wheelbases of 127.5 and 134.5 inches. Power came from a 320-cubic-inch inline engine making 90 bhp. Next up was the dashing Speedster Eight, offering lithe boattail and standard roadsters, plus phaeton, victoria, and sedan, all on a 134-inch chassis.

Speedsters cost the world -- $5200-$6000 -- so only 150 were built before the series was canceled after 1930. A 385-cid eight delivered 125-145 bhp in Speedsters. A 106-bhp version powered Custom and DeLuxe Eights on respective wheelbases of 140.5 and 145.5 inches. These were generally built with closed bodies, but were also available in phaeton, roadster, and convertible styles by Packard and various custom coach-builders. Prices here weren't quite the world, ranging from $3200 to over $5000. Then again, such sums bought a rather nice house at the time.

The 1931 Eighth Series comprised standard, Custom, and DeLuxe Eights. The standard line now offered "Individual Customs" on the 134.5-inch chassis. Included were a Dietrich convertible sedan and victoria, plus Packard's own cabriolet, town car, and landaulet styles. Standard models retained the 320 engine, now 10 bhp richer; Custom and DeLuxe again carried the 385 unit, now with 120 bhp.

The extra power came from modified intake and exhaust passages similar to those on the 1930 Speedsters. Other linewide mechanical changes included automatic Bijur chassis-lubrication system and a new quick-shift mechanism for the four-speed gearbox to reduce effort.

For more on defunct American cars, see:

- AMC

- Duesenberg

- Oldsmobile

- Plymouth

- Studebaker

- Tucker

Advertisement