It's a cliché that necessity is the mother of invention, but it's clichéd because it's true. Imagine that you live in a rural Southern town during the Great Depression. Crops have failed and work is scarce. The only thing you have is your car -- and it's a sweet one. It may just be an old Ford, but you've spent plenty of time working on it. You've sweated over the engine in the hot Georgia sun, scraping your knuckles while wrenching parts into place so many times that it seems like the engine is covered in equal parts blood and grease. That car is your world. It's your ticket to a better life.

Not only is the car a well-oiled machine, but you're also a great driver. In loosely organized races through the pastures and back roads of the country, you've beaten all comers -- or at least given them a run for their money. Now your skill has caught the eye of some connected individuals, and they have a job for you.

Advertisement

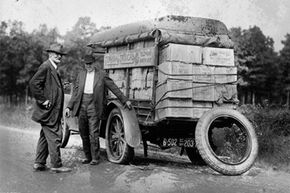

Even though prohibition is over, many towns in the South are dry. Selling liquor is illegal. And, even in parts where liquor can be sold, if you sell it without the authorities knowing, you don't have to pay taxes. That's more money in your pocket. So now you've got a job running homemade liquor -- moonshine -- into dry towns. You've got to get the liquor to the buyers and avoid the police. If you can't avoid the police or the federal revenuers, you've got to outrun them. It's just the job you and your car were made for.

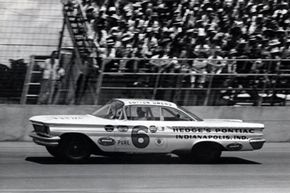

Running liquor wasn't uncommon during the 1920s and '30s. But here's where the story takes an interesting twist -- the same men who used their skills as drivers and mechanics to outrun the law used those same skills to found one of the most popular sports in the country: NASCAR. The need to make a living and the love of fast cars combined in the sport with one of the most colorful backgrounds imaginable. Trust us -- football and baseball didn't evolve from a heady combination of the need to outsmart police and the ability to have a great time doing it.

Those original cars raced on weekends in small towns throughout the South and spent the rest of their time as whiskey cars; souped up and filled with illegal liquor, they toured the South making deliveries and avoiding the law. The characters and technology behind the precursors to today's NASCAR race cars are as intoxicating as the liquor they carried.

Advertisement