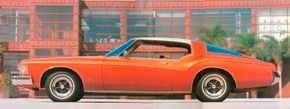

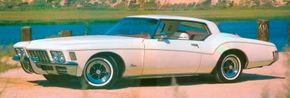

The 1971 Buick Riviera design was one that most people either loved or hated, and that’s still the case. The design was an attempt to capture the “classic” flavor of the old 1930s boattail roadsters, but critics argue that it just didn’t come off. Partisans, on the other hand, insist it did.

It has never been clear exactly who was responsible for styling the “boattail” Riviera of 1971-1973. Lee N. Mays, who fell heir to the car when he became Buick’s General Manager in 1969, cordially hated it. In later years, he wryly commented, “I could never find anyone who admitted they designed it.”

In retrospect, the concept appears to have originated with the Buick “Y-Job,” an experimental “show” car styled by Harley Earl and built during 1938; the resemblance to the 1963 Corvette Sting Ray is unmistakable.

Bill Mitchell, who had succeeded Earl as General Motors’ styling chief, was evidently the prime mover behind the boattail project, but it is unclear to this day who laid down the actual design.

Norbye and Dunne credit Donald C. Lasky, Dave Molls’ successor as Buick’s styling chief. But Jerry Hirshberg, in charge of Buick’s advance design studio at the time, has claimed the design as his own, while confessing that “I think the boattail was a mistake.”

In any case, according to Hirshberg, the original intent had been for this new Riviera to be a smaller car, based on the General Motors A-body. And when you think of it, a boattail built on the 112-inch chassis of the two-door Buick Skylark might well have been an exceptionally handsome automobile.

Over the years, the fastback design has generally been far more successful on smaller cars than on big ones.

A case in point is the American Motors Marlin of 1965-1967. AMC styling chief Dick Teague had developed a high-fashion show car called the Tarpon, to be displayed at the national convention of the Society of Automotive Engineers in 1964. Based on the 106-inch wheelbase of the compact Rambler American, the Tarpon was a beautifully proportioned little automobile.

But Roy Abernethy, who in 1962 had succeeded George Romney as president of the company, liked big cars. At his insistence the fastback was stretched a foot and a half to become the Marlin. Teague’s exquisite proportions were lost in the process, and the car was a dismal failure.

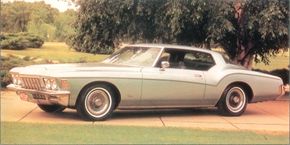

The wheelbase of the Riviera had grown in 1966 to 119 inches, up two inches from its 1963 measurement. For 1971, it was stretched again, this time to 122 inches.

Overall length was also increased a couple of inches compared to 1970, bringing it to 217.4 inches overall -- nearly nine and a half inches longer than the original edition.

Width swelled to 79.9 inches, more than five and a quarter inches greater than that of the 1963 car. The 1971 Buick Riviera had become a highway cruiser, almost identical in overall dimensions to the 1971 Chevrolet Impala.

If there was any practical benefit in all this, it came in the form of hip room, which was greater by nearly six inches in front and by more than three inches for back-seat passengers. Trunk space, likewise, was increased by 35 percent.

But Bill Mitchell -- the man who had inspired the boattail in the first place -- caustically observed that “What hurt the boattail was to widen it. It got so wide, a speedboat became a tugboat.”

And yet, unlike many large fastbacks, the boattail Riviera was not ill-proportioned. Although the design was unquestionably controversial, many observers have called it one of the most beautiful automobiles to come along in many years.

Full wheel cutouts relieved what might otherwise have been an unacceptable slab-sided look, and the long hood served to balance the Riviera’s sweeping fastback rear.

For its part, Buick touted the “aerodynamic styling. Longer. Wider. Daring new design. The 1971 Riviera is motion-sculptured giving an image of movement even when standing still. In a word: "excitement.”

Learn about 1971 Buick Riviera performance on the next page.

For more information on cars, see: