By late 1941, the jeep as we know it was coming together in leaps and bounds. However, Bantam was the only automaker that could meet the Army's ridiculous proposal of having a running prototype ready in 49 days. The reason for this was the singular effort of Karl Probst -- who was busy readying Bantam's pilot.

While all this was going on, the Army asked Bantam to build the remaining 69 cars from the original bid -- including eight with four-wheel steering -- without seeing the finished prototype. By confirming their order in advance, the Army did two things. First, this single act cut the silhouette of the original jeep, before Willys or Ford even had a chance to show their prototypes. More importantly, it forced Willys and Ford to get moving on their pilots lest they be left out of the process completely.

Advertisement

The Army Quartermaster, however, felt the need to diversify jeep production. So copies of Probst's blueprints were supplied to the rival firms despite the vehement protests of American Bantam. The Army did this on the premise that the design had become its property.

Bantam's distress was understandable enough, but the urgency of the situation was such that there was simply no time for the usual niceties. Willys and Ford would soon have prototypes of their own, offering competition to the Bantam. However, the sharing of the prototype drawings cut out a great deal of leg work for Willys and Ford, and took away Bantam's advanced development advantage.

Like Karl Probst at Bantam, Willys-Overland's Barney Roos had concluded that the Army's original weight limit of 1,300 pounds for its proposed new reconnaissance car was unrealistic. But unlike Probst, Roos also concluded that the specified completion date was also impossible to achieve, partly because the Spicer four-wheel drivetrain would not be easy for him to obtain. This explains why the Willys model was late coming out of the blocks.

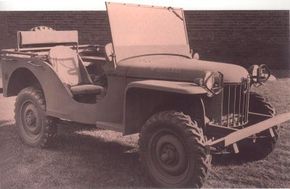

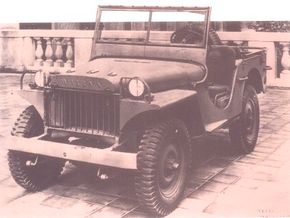

The Willys pilot, known as the "Quad" (an echo of the four-wheel-drive truck supplied to the military by Nash Motors during the First World War) was delivered to Holabird on November 13, 1940, followed 10 days later by the Ford "Pygmy."

Since both were based upon Karl Probst's design, it is hardly surprising that they looked almost exactly like the Bantam pilot whose testing had been completed the previous month. One obvious exception to this was the flat grille used by the Ford. The Willys, on the other hand, mimicked the rounded grill employed by the Bantam.

A. Wade Wells, in his 1946 book Hail to the Jeep, quotes Willys test driver Donald Kenower's account of the test exercise that followed the preliminary 4,000-mile highway run:

"The next part of the test was what they called cross-country. This was run in a field, at the camp, which they had fixed up to simulate extremely rough country, ditches, hills, etc. Our job had light springs and rode fairly well. The result was that they drove it about twice as fast as they did other similar vehicles, as the speed was regulated by how fast it was possible to go and still stay in the job."

(It is only fair to caution the reader that Wells was a Willys-Overland employee, so his observations may not have been entirely objective.)

Wells continues: "During the cross-country test the field became a mud lake due to continuous hard rains. At that time we found that the oil bath air cleaner was not properly mounted, and permitted dirt to get in the engine through the air inlet. Before this was discovered, the engine had been damaged, and in order to continue the test and avoid delay an engine was taken out of a Willys passenger car and installed in the pilot model, and it was again running on the course in a few hours."

Ford, meanwhile, had reservations about the project. By this time, the company was committed to larger, heavier passenger cars with much greater engine displacement than the Army specifications called for. But the Quartermaster believed that Ford's enormous productive capacity would ultimately be needed. So pressure was brought to bear, and in the end Ford entered the contest.

The Ford pilot car made use of what was by that time the company's only four-cylinder powerplant -- a modified version of the Fordson tractor engine. This unit, basically half of the Mercury V-8, was roundly criticized by Road & Track's John Bond for such shortcomings as "split valve guides, no adjustment for tappets, semi-steel pistons, no real concept of proper valve timing or even combustion chamber design."

Another problem Ford encountered was the fact that it did not have a suitable transmission. So, the old, non-synchro Model A gearbox was used -- rugged and reliable, but hopelessly outclassed by the competition.

The next section goes into more detail about the differences between the Willys, Bantam, and Ford early jeep designs.

For more information on Jeeps, see:

- History of Jeep

- Consumer Guide New Jeep Prices and Reviews

- Consumer Guide Used Jeep Prices and Reviews

Advertisement