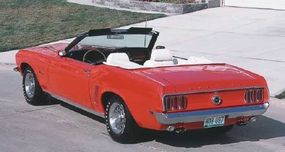

As rapidly as they had climbed in the early years, sales of Dearborn's sporty car were plummeting as preparations continued on what would become the 1969 Ford Mustang. Was Mustang losing it's magic? The question was particularly important to a new company president, recruited from a surprising source, who immediately made his mark with two of the greatest cars in performance history.

Success has many fathers, the old adage says, but Mustang had only one -- or so the public was told. We know better now, but there's no question that the Mustang's instant phenomenal success was a huge career boost for Lee Iacocca. By 1968 he had been moved up to executive vice-president of Ford's North American Operations.

Advertisement

But successful leaders usually have strong wills and egos to match, and one suspects that sudden fame encouraged Iacocca to push that much harder for the job he had always wanted: president of Ford Motor Company. There was just one problem. Iacocca was a brash outsider in a family-owned enterprise, and the head of that family didn't like being upstaged. As designer Gale Halderman told Collectible Automobile© magazine many years later: "Iacocca was credited in the press as the father of the Mustang and the savior of the company, which caused [chairman Henry Ford II] to start thinking to himself, "This guy's trying to take over."

Such was the background on February 6, 1968, when Ford announced that its chairman had selected a new president: veteran General Motors executive Semon E. "Bunkie" Knudsen. Detroit was astonished. Here was probably the most startling managerial shift since 1922, when Bunkie's father, William S. Knudsen, left Ford for Chevrolet after an argument with Henry Ford I. "Big Bill" quickly built Chevy into a Ford-beater, and his son made Pontiac number-three in the late Fifties before taking command at Chevrolet. Now Bunkie aimed to remake Ford. Ironically, he accepted HFII's invitation after being passed over as GM president in favor of Ed Cole.

Author Gary Witzenburg observed that "Knudsen, like Iacocca, was a hard-charging, dynamic, ambitious leader who…arrived at Ford amid a tornado of press and public attention and [was] full of big ideas on how to attack his former employer in the marketplace." Rumors of a management shake-up were flying even before Bunkie moved into Ford's "Glass House" headquarters. Though he did make some changes, there was no wholesale cleanout. But several Ford execs did resign after Knudsen came in, and Iacocca reportedly threatened to. Knudsen, for his part, was content to work with the Mustang's celebrated papa, but their relationship was uneasy at best, the two men clashing on several occasions.

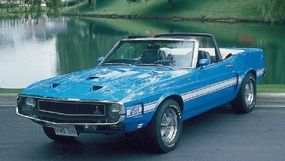

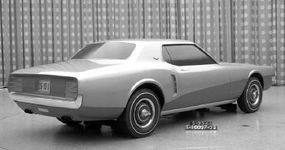

Knudsen was too late to influence the Mustang's planned 1969 redesign, which had been pretty much locked up for a year before he arrived. But he was able to add two very hot mid-season models while laying the groundwork for bigger, bolder future Mustangs. Knudsen loved burly high-performance cars, especially low, sleek fastbacks. He also loved NASCAR stockers and Trans-Am racers, perhaps because they resembled showroom wares.

Mustang sales had been waning since 1966, but Bunkie didn't seem concerned. "We are comparing today's Mustang penetration with [years] when there was no one else in that particular segment of the market," he explained. And he had thoughts on how to fire up sales. "The long-hood/short-deck concept will continue," he promised, but "there will be a trend toward designing cars for specific segments of the market." He also assured the press that Ford would continue in NASCAR and Trans-Am.

Bunkie, Larry, and "The Ultimate Mustang"

Almost immediately, Knudsen decided that Ford needed to develop "the killer street car," to use Witzenburg's term -- and that it should be a Mustang. To help create it, he hired designer Larry Shinoda away from GM and teamed him with Dearborn talents like Harvey Winn, Ken Dowd, Bill Shannon, and Dick Petit. With engineering assistance from Ed Hall, Chuck Mountain, and others, Shinoda's crew whipped up a bevy of eye-opening concept cars like the King Cobra, a slicked-down Torino fastback designed for high-speed stock-car racing, while feverishly working on Knudsen's ultimate Mustang.

Shinoda and Knudsen were old friends by now. They'd first met at Daytona Beach in 1956, when Bunkie took note of a very "trick," very fast Pontiac that Shinoda was working on. Shinoda, a teen-age hot-rodder in his native Southern California, knew how to shape a car for top straight-line speed and how to tune a chassis for top cornering speed. He came to Ford after working closely with GM design chief William L. Mitchell on various experimental projects and production cars including the 1963 Corvette Sting Ray and its '68 "shark" replacement. With all this, Shinoda's hiring was no less shocking than Bunkie's.

Want to find out more about the Mustang legacy? Follow these links to learn all about the original pony car:

- Saddle up for the complete story of America's best-loved sporty car. How the Ford Mustang Works chronicles the legend from its inception in the early 1960s to today's all-new Mustang.

- In 1967, the original pony car was up for its first major revamp. Learn how Ford retooled and updated the 1967-1968 Ford Mustang to meet public expectations and to keep pace with the competition.

- With sales down and criticism abounding, the Mustang struggled in the early '70s. Learn what went wrong (and what went right) for the 1971-1973 Ford Mustang.

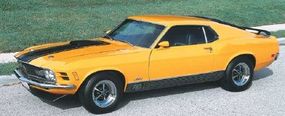

- The 1969 Ford Mustang Mach 1 428 Cobra Jet was the muscle car Mustang fans had waited for. Gallop into its profile, photos, and specifications.

Advertisement