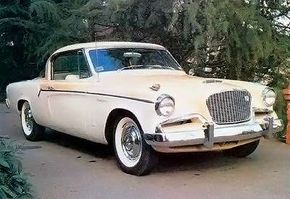

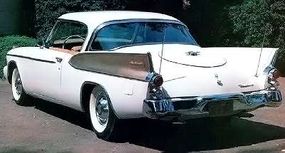

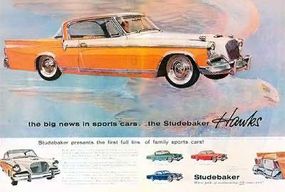

Depending on whom you talk to, the 1956-1961 Studebaker Hawk was either a clumsy, cluttered continuation of the breathtaking "Loewy coupe," or a remarkably clever repackaging job that introduced the sporty personal car to Americans years before Lee Iacocca ever thought about a Mustang. Even Studebaker partisans are divided on these cars, which bridged the style and time gaps between the memorable 1953-1954 original and Brooks Stevens' deftly re-styled 1962 Gran Turismo Hawk.

Advertisement

But most agree that it was horsepower and a continental flair that make these Hawks collectible automobiles today, not add-on fins and pseudo-Mercedes grilles. These low-slung, performance-oriented machines appeared at a time when Detroit was emphasizing bulk, chrome, and "road-hugging weight" -- and were thus completely out of step with contemporary values. But while John Q. Public mostly shopped elsewhere, a small group of discerning motorists learned to appreciate these cars. Their fans are still out there today.

Bowing in October 1955, the Hawk marked the end of the Loewy group's involvement with the design that had made Studebaker the industry's style leader three years earlier. Retaining the 120.5-inch-wheelbase chassis and basic bodyshell of the 1953-1955 Starlight/Starliner, the Hawk stood in sharp contrast to Studebaker's newly reskinned 1956 sedans and wagons, which still rode a 116.5-inch wheel base but looked far bulkier and more conservative.

Bob Bourke, the company's chief designer in the Fifties, stated: "Although I felt the 1956 Hawk series was an improvement over the heavily chromed 1955s, I still prefer the pure, clean appearance of the 1953s and 1954s." Actually, Studebaker's 1956 styling was quite understated for the time, but the Hawk looked like something from Europe. And unlike its predecessors, it bore no obvious styling relationship to other Studes at the front or rear. As Loewy's farewell to South Bend, the Hawk was striking, but it appeared only because Studebaker-Packard president James J. Nance had insisted on a full line of cars in all price ranges. For similar reasons, there were no fewer than four variations: Flight Hawk, Power Hawk, Sky Hawk, and Golden Hawk in ascending order of price, power, and plush.

On the next page, learn about the debut of the 1956 Studebaker Hawk.

For more information on cars, see:

- Classic Cars

- Muscle Cars

- Sports Cars

- Consumer Guide New Car Search

- Consumer Guide Used Car Search

Advertisement