An ordinary four-stroke engine dedicates one stroke to the process of air intake. Three things happen during this process:

- The piston moves down.

- This creates a vacuum inside the cylinder.

- The vacuum causes air at atmospheric pressure to be sucked into the combustion chamber.

Once air is drawn into the engine, it must be combined with fuel to form the charge – a packet of potential energy that can be turned into useful kinetic energy through a chemical reaction known as combustion. The spark plug initiates this chemical reaction by igniting the charge. As the fuel undergoes oxidation, a great deal of energy is released. The force of this explosion, concentrated above the cylinder head, drives the piston down. The motion created by the movement of the piston is eventually transferred to the wheels.

Getting more fuel into the charge would make for a more powerful explosion. But you can't simply pump more fuel into the engine because you need an exact amount of oxygen burn a given amount of fuel. When idling or cruising at a constant speed, the mixture is 14.7 parts of air to 1 part fuel. When you need more power, such as accelerating to pass on the highway, the air-fuel ratio is more like 12:1. If you want to set records in the quarter-mile, however, you'll need to add more air so you can add more fuel.

That's the job of the supercharger. Superchargers increase intake by compressing air above atmospheric pressure without creating a vacuum. This forces more air into the engine, providing a boost. With the additional air, more fuel can be added to the charge, and the power of the engine is increased. Supercharging adds an average of 46 percent more horsepower and 31 percent more torque. In high-altitude situations, where engine performance deteriorates because the air has low density and pressure, a supercharger delivers higher-pressure air to the engine so it can operate optimally.

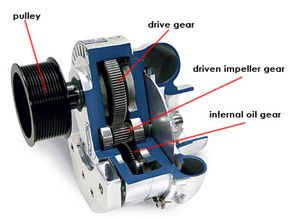

Unlike turbochargers, which use the exhaust gases created by combustion to power the compressor, superchargers draw their power directly from the crankshaft. Most are driven by an accessory belt, which wraps around a pulley that is connected to a drive gear. The drive gear, in turn, rotates the compressor gear. The rotor of the compressor can come in various designs, but its job is to draw air in, squeeze the air into a smaller space and discharge it into the intake manifold.

To pressurize the air, a supercharger must spin rapidly – more rapidly than the engine itself. Making the drive gear larger than the compressor gear causes the compressor to spin faster. Superchargers can spin at speeds as high as 50,000 to 65,000 rotations per minute (RPM).

A compressor spinning at 50,000 RPM translates to a boost of about 6 to 9 pounds per square inch (psi). That's 6 to 9 additional psi over the atmospheric pressure at a particular elevation. Atmospheric pressure at sea level is 14.7 psi, so a typical boost from a supercharger places about 50 percent more air into the engine.

As the air is compressed, it gets hotter. Hotter air is less dense and can't expand as much during the explosion as cooler air. This means that it can't create as much power when it's ignited by the spark plug. For a supercharger to work at peak efficiency, the compressed air exiting the discharge unit must be cooled before it enters the intake manifold. The intercooler is responsible for this cooling process. Intercoolers come in two basic designs: air-to-air intercoolers and air-to-water intercoolers. Both work just like a radiator, with cooler air or water sent through a system of pipes or tubes. As the hot air exiting the supercharger encounters the cooler pipes, it also cools down. The reduction in air temperature increases the density of the air, which makes for a denser charge entering the combustion chamber.

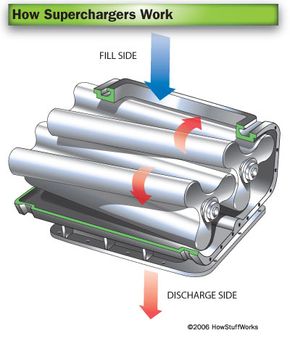

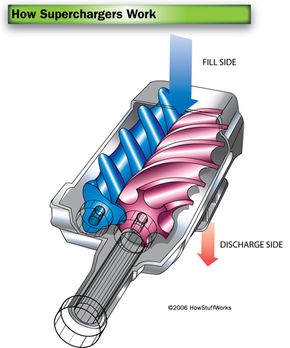

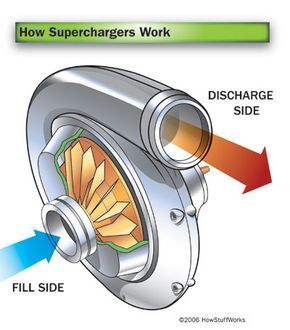

Next, we'll look at the different types of superchargers.