Key Takeaways

- The first Belvedere model was a premium hardtop coupe from Plymouth.

- Plymouth's postwar challenges included a late start, competition and leadership decisions affecting sales.

- Changes in design, features and performance took place from 1951 to 1958.

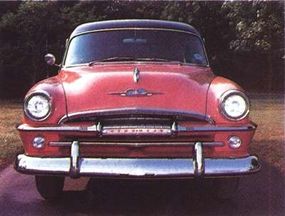

From premium early-Fifties hardtop coupe to fiery top-line series, there's a lot of variety to be found under Plymouth's Belvedere badge. Here's a look at the 1951-1958 Plymouth Belvedere, the first of the breed, all interesting and long-overlooked collectibles.

Belvedere is hardly a household word. Some may recognize it as the name of a fictional butler portrayed in a 1980s TV series, while others know it as the northwest Illinois town (spelled Belvidere) where Chrysler has a plant. But in the Fabulous Fifties, Belvedere usually meant Plymouth's best.

Advertisement

The first Belvedere was a two-door hardtop arriving a year behind Chevrolet's Bel Air and two years after GM started the pillarless-coupe craze. Not that there weren't other Johnny-come-lately hardtops: Ford's Victoria also bowed for 1951, Studebaker's Starliner a year later. But Plymouth had a habit of being late in the postwar years, often to the peril of Chrysler Corporation itself.

Plymouth had started late. Introduced on July 7, 1928, it was 25 years behind Ford and 16 years younger than Chevy. Yet by the end of 1929, Walter P. Chrysler's new low-price contender had skyrocketed to 10th place in an industry field of 36. Sales declined in 1930, but not as much as most makes, and Plymouth finished fifth, ahead of sister divisions Dodge and Chrysler as well as Essex, Studebaker, and Nash. Mid-1931 brought the PA series, with fresh styling and the smoothness of "Floating Power" engine mounts; Plymouth overhauled Buick and Pontiac to claim third.

Two years later, Plymouth switched from fours to sixes, invited buyers to "look at all three," and promptly doubled sales even as the Depression bottomed out. Production was well past the half-million mark by 1936, about equal to combined Buick-Olds-Pontiac output.

Of course, the target was never those GM makes but Ford. Chrysler was out to make Plymouth No. 2, right behind Chevrolet, and it nearly succeeded with an attractively restyled 1940 line that sold only 15 percent behind Ford. Yet Dearborn's lead was 42 percent by 1947 and better than two-to-one just three years later, when Buick threatened to grab third. By 1954, Plymouth was fifth (behind Buick and Olds) and trailed Ford by an astonishing 71 percent.

Styling wasn't solely to blame for Plymouth's postwar plunge, but it's as good a place to start as any. Which inevitably brings up iron-willed Chrysler president Kaufman Thuma Keller. K.T., as he was always called, had come up through the manufacturing ranks and firmly believed in practical products. So though he appreciated fine art, his cars invariably sacrificed beauty for utility. "Smaller on the outside, bigger on the inside" appealed to K.T., who thought people wanted cars they could ride in with their hats on.

Chrysler's all-new 1949 fleet thus arrived with high, boxy bodies, lots of headroom -- and stodgy looks. But the public really wanted shiny, low-slung torpedoes, and Keller's "three-box" cars began losing ground in 1950, when competition heated up with the end of the postwar seller's market. All Chrysler brands felt the heat. Plymouth got burned.

Favoritism compounded the problem. With the return of civilian production in the late Forties came shortages of certain raw materials, notably sheet steel. For multi-line automakers like Chrysler, this raised the question of whether to allocate available supplies among all operations or only those that could turn the biggest and fastest profits.

Advertisement