Key Takeaways

- The 1965-1968 Dodge Monaco and Monaco 500 pursued Pontiac Grand Prix's winning style.

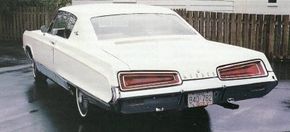

- Dodge's catch-up efforts included new name "Monaco" and unique taillight design.

- Despite efforts, Dodge Monaco faced tough competition and eventually met its demise in 1969.

There was no denying that the Pontiac Grand Prix of the 1960s had a sense of style other automakers wished they could duplicate. Even though the nature of the Grand Prix's winning style was elusive, it didn't prevent others in Detroit from pursuing it. For Dodge, this pursuit took the form of the 1965-1968 Dodge Monaco and Monaco 500.

However, despite their best efforts and to the dismay of other medium-priced makes, the 1960s truly belonged to Pontiac. Ever since Bunkie Knudsen tore off the hallowed "Silver Streak" hood trim for 1957, Pontiac had been on the rise. Swiftly, seemingly from nowhere, a winning combination of good looks and deft marketing lifted the "Wide Track" brand to a secure third place in total industry sales.

Advertisement

Two long-established competitors, Dodge and Mercury, had to scramble just to stay in the race, a race made all the more difficult by the fact that both virtually abandoned the medium-priced market tor 1961-1962, leaving all the glory -- and most of the profits -- to Pontiac. Mercury's run at Pontiac is another story, but Dodge's catch-up efforts included a new name -- Monaco -- and the labors of Jeffrey Godshall as one of the "Dodge Boys" in the styling studios.

"It was in early February 1963, during one of the coldest Midwestern winters in memory, that I achieved a goal I'd been aiming at since I was 14 years old: becoming a designer ('stylist' back then) for Chrysler Corporation," says Godshall. "It had taken a long eight months since graduating from the Carnegie Institute of Technology in Pittsburgh, but I'd finally landed the job I'd set my heart on. After a few months in a catch-all orientation studio under Dick Macadam (later Elwood Engel's successor as Chrysler design vice-president), I was transferred to my first production assignment in the Dodge Exterior Studio."

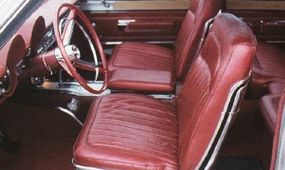

"I was lucky to get this plum position," he continues, "given the intense ongoing rivalry between siblings Dodge and Plymouth, a rivalry keenly felt by their respective stylists. In mid-1963, the Dodge studio was putting the final touches on its 1965 models, the "A" series in Chrysler Engineering-speak. Against one wall stood the clay buck for the new B-body Coronet, the most vanilla-looking car I'd ever seen. Mid-studio, work was proceeding on a nicely facelifted A-body Dart. But on a platform at the west end of the long room sat the one really new car to be seen: the big C-body Dodge."

Advertisement