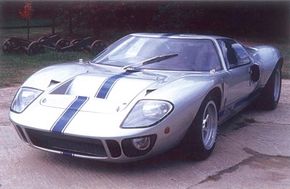

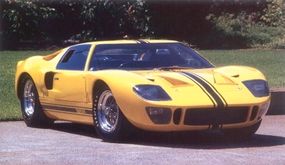

Almost everyone is familiar with the shorthand history of the 1964-1967 Ford GT as it has been presented so many times since then. Basically, it goes like this: Having been rebuffed by Enzo Ferrari in their attempts to purchase his company and the glory attending it, Henry Ford II and his minions decided to add big-time sports-car racing to their competition plate -- already crowded with participation in NASCAR, Formula 1, the Indianapolis 500, and international rallying -- by buying up another established builder of racing machinery, one that wouldn't balk at being associated with the Ford name.

Advertisement

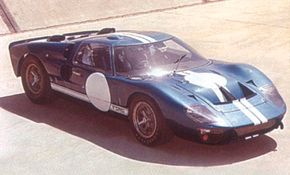

Over in England, Eric Broadley's Lola Cars, Ltd. had just introduced a sleek, Le Mans-ready mid-engine coupe, providentially fitted with an American Ford V-8 engine. Ford, looking for the shortest distance between idea and success, bought up Mr. Broadley's little shop, dressed up the Lola Mark 6 GT a bit, and, lo and behold, a mere 10-figure cash expenditure later, was able to steamroller its way to victory at Le Mans.

A first indication that the popular fable may not be the real, a complete story of the GT can be found in the spring 1964 issue of Automobile Quarterly. There, in a piece curiously titled "America Goes Grand Prix," Ford's Roy Lunn lays out some of the thinking behind the GT's development. It's all very general, of course, and slightly disjointed in places, as if edited down from a much larger story.

The AQ story had been culled from a paper submitted to the Society of Automotive Engineers plus, apparently, some material prepared for a lecture Lunn was to present. But within the descriptions of aerodynamic research, project design parameters, and other details was a paragraph that began with the words, "By July, 1963, a basic design and style had been established at Dearborn..."

Fords had won races on lots of tracks in lots of series by the early 1960s, but the 24-hour sports-car endurance classic at Le Mans was not on that list. Henry Ford II wanted to change that.

Dearborn? That's a heckuva long way from Slough Trading Estates in England.

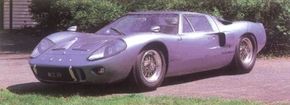

The story's trail led from that innocuous sentence to retired Ford project engineer Bob Negstad, who was assigned to what would become the Ford GT project in its earliest days. He agrees that the impetus for the project came in part from Ferrari's refusal to join Prancing Horse to Blue Oval. But he is adamant that the similarities between the Lola Mark 6 and the Ford GT are largely coincidental.

Lola was brought into the project, Negstad asserts, because Eric Broadley was a "brilliant fabricator." He ended up doing much of the construction and assembly work on the Ford GT prototype. But it was not in any way his creation.

"Broadley was technically naive," Negstad says, "a trial-and-error man" working in a "terribly old, obsolete building lit by a single 40-watt bulb." The attraction for Ford was not Broadley's design expertise, but rather his ability to quickly build what they wanted, plus the availability of a car of somewhat similar configuration that could serve as a driveable test bed while Ford's own design was coming together.

For more information on the the 1964-1967 Ford GT classic car, continue on to the next page.

For more information on cars, see:

- Classic Cars

- Muscle Cars

- Sports Cars

- New Car Search

- Used Car Search

Advertisement