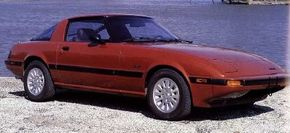

In greeting the second-generation, 1986-1988 Mazda RX-7, some journalists felt compelled to state that the original would be tough to follow. Unsaid was the equally obvious fact that the ’86 couldn’t hope to have its predecessor’s impact, for the market had changed a lot since 1978 -- more crowded and competitive than ever. Yet with a little perspective, the second-generation emerges as not only a more mature RX-7 but an eminently desirable one in its own right.

It was born in 1981 as Project P747 (a purely arbitrary number chosen to confuse outsiders). Rotary power, front/mid-engine layout, rear drive, unit construction, and close-coupled hatchback coupe format were never in doubt, but American feedback on the original RX-7, gleaned from several U.S. trips by chief engineer Akio Uchiyama, gave Mazda a whole new perspective on "RX-7ism."

Three possibilities were hatched for P747: a continuation of the existing model, an all-new "high-tech" car with electronic suspension and rear transaxle, and something in between. The last ultimately won out, but the influence of Porsche’s 944, which arrived in the program’s second year, would be undeniable. Exterior and interior design, features, packaging, and other essentials were determined through a long series of consumer meetings, with counsel from Mazda’s California-based U.S. design center.

The Porsche’s styling had "tested" well, so the new Mazda RX-7 looked much like the 944 in front. But the central body bore Porsche 928 overtones, while the compound-curve hatch and bold taillights looked like Chevrolet Camaro copies.

A disappointed press termed it all "timid" and "derivative," but at least the new shape was slipperier. The claimed drag coefficient was 0.31, and the optional Sports Package with front air dam, rocker skirts, and loop-type spoiler cut that to a commendable 0.29.

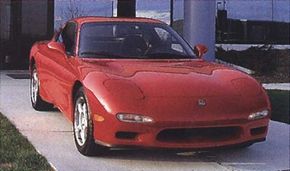

More exciting things hid beneath. Base power was now the six-port 13B rotary with electronic fuel injection, first seen in the U.S. on the ’84 GSL-SE but with 11 more horsepower and 6 percent more torque. And there was a production first: an intercooled "Turbo II" version packing an extra 38 horsepower in U.S. trim, a remarkable 182 bhp total. (The blown Wankel was only new to America, however, as Mazda had offered a first-generation "Turbo I" model in Japan.)

The extra muscle was welcome. The base ’86 weighed about 240 pounds more than the comparable ’85, and the Turbo was some 225 pounds heavier still. Dimensions stayed roughly the same though. The Turbo wasn’t available with automatic, but non-turbos were: a new 4-speed overdrive unit, replacing the previous non-OD 3-speeder.

The chassis offered more Good Stuff. Rack-and-pinion steering ousted recirculating ball, and its available power assist was a new electronic system that varied effort with vehicle speed and road surface changes. Front suspension was a simpler MacPherson strut/A-arm setup.

Out back, the old live axle was discarded for a new independent Dynamic Tracking Suspension System (DTSS). A rather complex semi-trailing-arm arrangement, it induced a small amount of stabilizing rear-wheel toe-in under high lateral loads and minimized camber changes in cornering, long a problem with this geometry.

An intended electronic ride control materialized as Auto Adjusting Suspension (AAS), two-stage manual/automatic shock damping. Finally, all models got low-pressure gas-filled shocks and disc rear brakes instead of drums, vented on the Turbo.

U.S. model choices expanded with the addition of the 2 + 2 package previously restricted to Europe and Japan. It and the familiar two-seater were offered in normally aspirated base form or as plusher GXLs with standard AAS, power steering, and a host of creature comforts.

The Sports Package, which also included power steering and firmer suspension, was limited to the base two-seater, but a Luxury Package with power sunroof and mirrors, premium sound system, and alloy wheels was optional for both it and the 2 + 2. The Turbo was a two-seater only.

Styling aside, the new Mazda RX-7s earned rave reviews. The ride was still a bit firm perhaps and the cockpit too tight for tall types, but the normally aspirated cars were usefully faster and the Turbo was a real flyer, more than a match for the 16-valve 944S in the inevitable comparison tests. One magazine said the new DTSS "occasionally out-tricks itself on the race track," but most critics agreed the new RX-7 was grippier, more nimble, and more forgiving than the old. One said it "raises the standards for sports-car performance."

The second-generation story is far from finished at this writing, and it keeps getting better. The main 1987 development was a new extra-cost anti-lock braking system for the Turbo, GXLs, and Sports Package. Also, a two-seat SE arrived during the year with mid-level trim, extra equipment, and special pricing to combat "sticker shock" caused by worsening yen/dollar exchange rates.

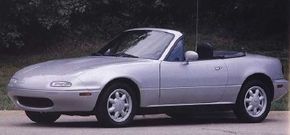

The plot thickens for 1988 with the first factory-built RX-7 convertible -- and rumors that Mazda may build RX-7s exclusively in the U.S., since that’s where most are sold anyway and sports-car demand is now nearly nil in Japan.

Whatever happens, the second-generation story is already a happy one. The original Mazda RX-7 may have been tough to follow, but in this case, success has bred success.

To learn more about Mazda and other sports cars, see: