The rapidly improved fortunes of the Ford Mustang from 1982 through 1986 mirrored those of Ford Motor Company itself. After teetering on the financial brink, Ford not only roared back to profitability, it became the most profitable outfit in Detroit. By 1987 it was earning more money each year than giant General Motors -- and on only half the sales volume. Critics were baffled, stockholders relieved, the automotive press impressed.

There was no secret to this. Like Chrysler under Lee Iaccoca, Ford under Don Petersen (who moved up to chairman in 1985) became more efficient, closing old factories, modernizing others, slashing overhead, and laying off workers (only to rehire some later).

Advertisement

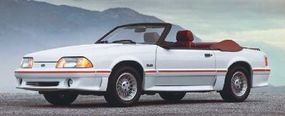

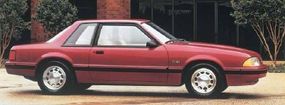

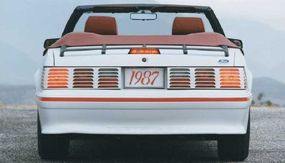

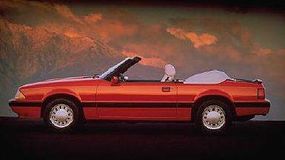

Though such steps were almost always painful, there was no choice in the face of unprecedented foreign competition. But where Chrysler put all its chips on one basic platform, the adaptable K-car, Ford trotted out a slew of new models with much broader sales appeal.Part of that appeal stemmed from a new aerodynamic styling signature instigated by Jack Telnack. It proved so popular that he was promoted in mid-1987 to replace Don Kopka as design vice-president for the entire company. Telnack's passion for "aero" had a practical side.As he had shown with the '79 Mustang, reducing air drag improves fuel economy. And as CAFE standards were not going away, that was still vital in the 1980s. But shapes born of the wind tunnel also gave Ford a way to stand apart from the herd at a time when design -- good design -- was again influencing sales more than EPA mileage numbers.Sure enough, amidst a sea of mostly square-rigged Chrysler products and lookalike GM cars, buyers flocked to smooth, unmistakable new Dearborn offerings like the 1983 Thunderbird and especially the 1986 Ford Taurus and Mercury Sable, affordable midsize sedans that looked like pricey German Audis.But the key to Mustang's success in these years was performance, not styling. Of course, it helped greatly that an economic recovery took hold in 1982, boosting personal income even as inflation, interest rates, unemployment, and especially gas prices all came down.

As we've seen, Ford also helped Mustang's cause with the same sort of relentless refining that Porsche used to keep its Sixties-era 911 sports car so evergreen. This not only involved more power almost every year but also new features and options, plus much improved workmanship.Yet the more things stay the same, the harder they can be to change, to paraphrase an old saw. Even as it got better and better, Mustang increasingly seemed a relic of Ford's past -- and ever more dated next to newer sporty cars. But sales were on the upswing, and nostalgia was a big factor, even for younger types who had missed "Mustang Mania" in the Sixties.

Still, Ford fretted over what would happen to sales should the market suddenly reverse again or if competitors mounted a strong new challenge. With all this, Ford reasoned, a next-generation Mustang ought to appear by 1989 at the latest.

In an unthinkable move, Ford originally sent the design duties outside of the country. On the next page, find out how the Mazda-designed car that became the Ford Probe almost wore a Mustang badge.

Advertisement