In 1963, Ferrari employed approximately 450 people and made 598 cars. The American divisions of the Ford Motor Company employed 175,000 and made 2.1 million cars.

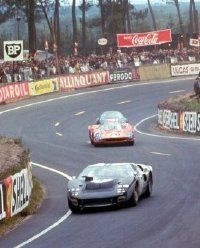

Yet, the model that Ford wanted more than anything else that fateful year was one with a Ferrari name on it. Indeed, a Ford buyout of Ferrari came very close to happening, but unraveled at the last minute, causing Ford to create its own legend: the GT40.

Advertisement

So why would one of America’s most powerful companies, one that, as a Ford executive put it recently “lost more [cars] in rounding errors than Ferrari made in a year,” want to acquire Ferrari?

The answer is simple: Mystique. In the early 1960s, no other firm so perfectly represented the concept of winning, technology, performance, and high style. And that’s just as true today.

The magic of the Ferrari legend starts with its founder, Enzo Ferrari. He was called an “agitator of men” by noted ex-Ferrari engineer Giotto Bizzarrini, and characterized similarly by scores of others. In his domain, Ferrari was a master psychologist who would do almost anything to extract the most from his employees.

Famed designer and coachbuilder Sergio Pininfarina was just 26 when he started working with Ferrari in 1952. He remembered visiting the factory numerous times after a sports-car win or a Formula 1 victory. Pininfarina often found Enzo in the racing department or on the production line barking orders, being as hard as ever on his men.

But when the coachbuilder visited the factory after a defeat, Ferrari was complimenting his troops for giving their all.

It took Pininfarina a bit to grasp what Ferrari was doing: Enzo didn’t want his subordinates to relax when it was the perfect time to do so. And he recognized when to motivate through positive reinforcement. Ferrari’s employees were willing to work night and day for him, and often did.

Enzo was born in the central Italian town of Modena on February 18, 1898, the younger of two children. That Ferrari and his small firm achieved worldwide fame surprised him and his family. “We lived in a modest house in the suburbs,” he wrote in his memoirs, “four rooms over my father’s metalworking business ... I shared one of the rooms above the workshop with my brother Alfredo and we were woken up by the hammering every morning when the men started work.”

In his earliest years, Ferrari had an aversion to school and enjoyed target shooting and roller-skating. Then the nascent automotive world hit his radar screen in 1908 “… when my father took me to my first automotive race. The crowds were all shouting for the No. 10 car driven by Felice Nazzaro who won the race. My father and brother were always talking about cars and I got more and more interested as I listened to their talk.”

Ferrari was hooked when he saw his next race a year later. “[B]eing that close to those cars and those heroes,” he wrote, “being part of the yelling crowd, that whole environment aroused my first flicker of interest in cars.”

It would be 10 years before Ferrari took the first unnoticeable steps to worldwide fame. His father wanted him to be an engineer, but young Enzo was more interested in a life in opera, as a tenor, or one in journalism, as a sportswriter. By age 16, he was freelancing for several newspapers.

In 1917, Ferrari was drafted into the army. He returned home with a severe illness that left him hospitalized. His father and brother had passed away two years earlier, so after recovering, Enzo headed to Turin, some 150 miles to the north, to find work.

Turin was well on its way to becoming an industrial center in Italy, thanks in great part to Fiat. By the mid 1920s, Fiat was Italy’s dominant industrial concern, and its cars actively raced around the world, often with great success.

Ferrari traveled to the bustling city to try for a job with Fiat, a letter of introduction in hand from his commanding Army officer. He was turned down, but soon found work at a small firm in Bologna that stripped trucks for their chassis, then used them for cars.

That job found Ferrari traveling to northern Italy’s other economic engine. Milan was some 100 miles west of Turin, and one of Ferrari’s favorite haunts was the Vittorio Emanuele bar, a well-known hangout for racing drivers and others in the automotive world. Enzo may have been a bit green, but the first sprinklings of his charisma were starting to show through. He was a good talker in the social setting, and soon found himself hired on as a test driver by the Milan automaker, Costruzioni Meccaniche Nazionali.

Find out how Enzo Ferrari fared as an Alfa Romeo driver on the next page.

For more great information on Ferrari, see:

- How Ferrari Works

- Ferrari Cars

- Other Cars With Ferrari Engines

- Ferrari History and Biographies

- Ferrari Pictures

- Ferrari Road Cars

- Ferrari F1

- Ferrari Sports Racing Cars

Advertisement